Articles

The Fraught Process Of Naming Beers

This is an article Mike Drumm wrote for Brewing Industry Guide: The Fraught Process of Naming Beers www.brewingindustryguide.com

Each new brewery that opens in the United States means new beers that need names. Finding ones that aren’t already taken or run up against a trademark isn’t difficult. Do the legwork in advance to save headaches and possible legal fees down the line.

“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” If Shakespeare’s Juliet were alive today (and not fictional), maybe she could consult with craft breweries on naming their beers (fun fact: Romeo and Juliet was written in the late sixteenth century; approximate number of breweries in the United States in the sixteenth century: 0).

Unless you are living under a rock, you know that craft breweries have experienced explosive growth throughout the United States (5,562 breweries to date, and another 2,700 in planning as of July 2017). These breweries are also brewing an unprecedented variety of beers. Each of these beers is a trademark. “A trademark includes any word, name, symbol, device, or any combination, used or intended to be used to identify and distinguish the goods/services of one seller or provider from those of others and to indicate the source of the goods/services” [emphasis added].

For a trademark to serve its purpose and distinguish one seller’s goods from another, no other seller of the same good can have the same trademark. This includes hops puns. With this many breweries and beers, it is inevitable that breweries will—intentionally or not—adopt names with common words or other elements.

History Lesson

The year was 2004 (1,468 U.S. breweries were in existence). Donald Trump was firing people in the first season of The Apprentice. Barbie and Ken had just ended their forty-three-year romance (they reunited in 2006). Janet Jackson experienced a wardrobe malfunction during the halftime of the Super Bowl.

Collaboration Not Litigation Ale was born. Avery Brewing brewed a beer named Salvation. Russian River Brewing also brewed a beer named Salvation. Instead of filing a lawsuit, these breweries collaborated. According to Avery Brewing, “In April 2004, in a top-secret meeting at Russian River Brewing, we came up with the perfect blend of the two Salvations,” and the result was Collaboration Not Litigation Ale.

This collaboration was not the result of lawyers angrily arguing over who had the legal right to the name Salvation for their beer but was a result of two brewers getting together to settle a legal issue and producing a positive result to the benefit of both parties (and all the consumers, who no doubt appreciated the end result as well).

Fast-forward seven years to 2011 (2,033 U.S. breweries were in existence). Sam Calagione stated in an interview that the craft-beer industry is “99 percent asshole-free” (for purposes of this article, we will refer to the remaining one percent as “@holes”). This translates into 20.33 @holes in 2011.

Changing Times

Jump ahead only one year to 2012 (2,456 U.S. breweries, with 24.56 @holes tagging along) when Coronado Brewing Company filed a lawsuit against Elysian Brewing Company over the IDIOT trademark.

One more year into the beer journey (2013—2,917 U.S. breweries, with 29.17 @holes introducing themselves), Magic Hat Brewing Company filed a lawsuit against West Sixth Brewing over the 9 and 6 logo trademarks; TI Beverage Group filed a lawsuit against Clown Shoes Brewing over the VAMPIRE trademark. Twelve months later (2014—3,464 U.S. breweries, with 34.46 @holes making their presence known), DuClaw Brewery filed a lawsuit against Left Hand Brewing Company over the SAWTOOTH and BLACK JACK STOUT trademarks.

In 2015 (4,548 U.S. breweries, with 45.48 @holes along for the ride), Lagunitas Brewing filed a lawsuit against Sierra Nevada over its IPA trademark; Colorado’s Fate Brewing filed a lawsuit against Arizona’s Fate Brewing over the FATE BREWING trademark; Brooklyn Brewery filed a lawsuit against Black Ops Brewing over the BROOKLYN BLACK OPS trademark; New Belgium filed a lawsuit against Oasis Brewing over the SLOW RIDE trademark.

During 2016 (5,301 U.S. breweries, with 53.01 @holes fermenting on the sidelines), Side Project Brewing filed a lawsuit against Modern Brewery over the light bulb logo trademark; Prescott Brewing filed a lawsuit against Hometown Brewing over the HOMETOWN trademark; Eel River Brewing filed a lawsuit against Duck Foot Brewing over the CALIFORNIA BLONDE trademark; Real Ale Brewing filed a lawsuit against Fireman’s Brew over the FIREMANS #4 trademark.

In 2017 (5,562 U.S. breweries, with 55.6 @holes solidly established in the industry and +27 @holes in planning), Shipyard Brewing Company filed a lawsuit against Logboat Brewing Company over the trademark SHIPHEAD; Moosehead Breweries filed a lawsuit against Hop’n Moose Brewing Company over MOOSE logo trademark.

Meander now to 2018 (between 5,562 and 8,262 U.S. breweries and between 55.62 to 82.62 @holes gracing the industry) when Stone Brewing filed a lawsuit against MillerCoors over the trademark STONE.

Stop the Madness

There are now 26 percent more breweries (and @holes) than there were in the Collaboration Not Litigation days. And more are coming every day. But trademark litigation doesn’t have to follow this same upward trend because the craft-beer industry is not running out of beer names. The industry is just getting lazy and throwing creativity out the window.

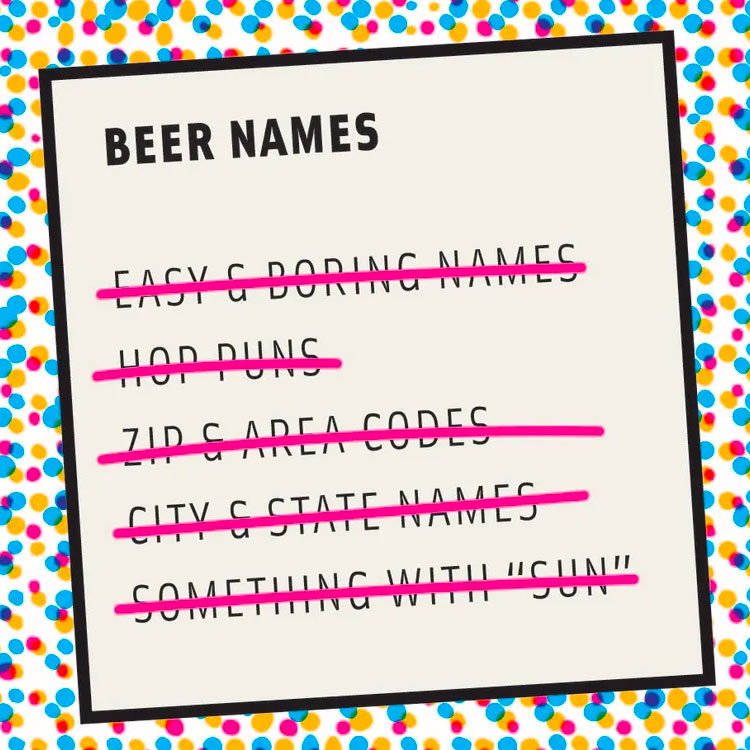

Easy names are gone. Boring names are gone. And most likely, the hops puns are gone (unless you are really creative, for instance Hophazardnesses). But this is a good thing. The craft-beer space is getting competitive and saturated in certain markets. Craft breweries are competing with 5,561 others (some of whom are very large breweries). Distinctive brands can help breweries stand out in the crowd.

Boring names can also imply boring beer. And easy beer names are not memorable. This means zip codes and area codes are gone (but not Morse Code). City and state names are gone, too (but not imaginary places such as Beer Attorney Land Lager). Sorry. But how many different sun* beers have you had that you distinctively remember (ratebeer.com currently has 6,997 results for “sun” in beers)? Compare that with the first time you had Pliney the Elder or Arrogant Bastard.

To test this boring and not memorable hypothesis, take the most boring-named beer that you have in your taproom and rename it “Don’t Buy this Beer [insert beer style]” for one week. See whether sales for that beer go up and whether people talk about the new branding. You can change the name the following week to “Memorable Boring Beer Test [insert beer style].”

A Plethora of Possibilities

In 2010, researchers from Harvard University and Google (back when there were only 1,813 U.S. breweries in existence) estimated a total of 1,022,000 words in the English language and that this number would grow by several thousand each year. That’s 1,022,000 single-word beer names available (for instance, Boffola Brown). Combine two of those words, and you have a lot more options (for instance, Imaginary Chore Cherry Stout).

The online combination formula maxed out at 100,000 total words, producing more than 4,999,950,000 two-word combinations. These more than 4.9 billion potential beer names do not even include made-up words (such as Unlightening Porter). Or three- or four-letter words (such as I Had To Hefeweizen and Long Forgotten Pen Pal Pilsner). Or phrases (such as Drinks From a Straw Dunkel). Or words in dead foreign languages (such as Impavidus).

Google It and Then Some

Google was founded in 1998 (in the early days when there were only about 1,514 U.S. breweries) and introduced its search engine to the world. While not its primary intended purpose, this search engine can drastically reduce the number of beer-trademark lawsuits.

Once you think you have a name from the possibilities above, a Google search of a proposed beer name can quickly let you know whether a name is available. Generally, if a beer trademark is being actively used, it should appear on a Google search (usually on a brewery’s website or a beer-review website).

Your search should also include other alcohol products (unfortunately, the United States Patent and Trademark Office views all alcohol the same as it relates to trademarks). Key search terms should include “[Proposed Beer Name] beer,” “[Proposed Beer Name] brewery,” “[Proposed Beer Name] wine,” “[Proposed Beer Name] alcohol,” and “[Proposed Beer Name] spirits.” You get the idea.

If you do not find any relevant uses, don’t stop there. Dig a little farther. It is easy to determine whether you cannot use a name for a beer trademark because you’ve found a conflicting use. It is harder to determine whether a trademark is available because you are looking for the absence of a conflicting use. Or, to put it a different way, looking for something is easier than looking for nothing.

The TTB Public COLA Registry is also a good place to search proposed beer names to see whether there are any pending labels with a similar name. Round up your efforts with one final search on the United States Patent and Trademark database (uspto.gov) to see whether there are any pending or registered trademarks that would cause an issue with your proposed trademark.

Grab a pint of Boring is Bad brew or a bomber of Creativity and Searching Kölsch and help the craft-beer industry return to the days of Collaboration Not Litigation. Or as Juliet, the not-dead and not-fictional beer-naming consultant, might say, “O Beer Name, Beer Name! Wherefore art thou Beer Name? Deny thy infringement and research thy name.”

And don’t be an @hole!